Post by Brett Peto

The alarm clock is ready to ring for the periodical cicadas of Lake County. The previous mass emergence of these impressive bugs in 2007 set the alarm for 2024. During spring and summer 17 years ago, millions of cicadas tunneled out of the soil, crawled up trees, sang, mated and completed their life cycle. This will be a magical year for their offspring.

A True Bug

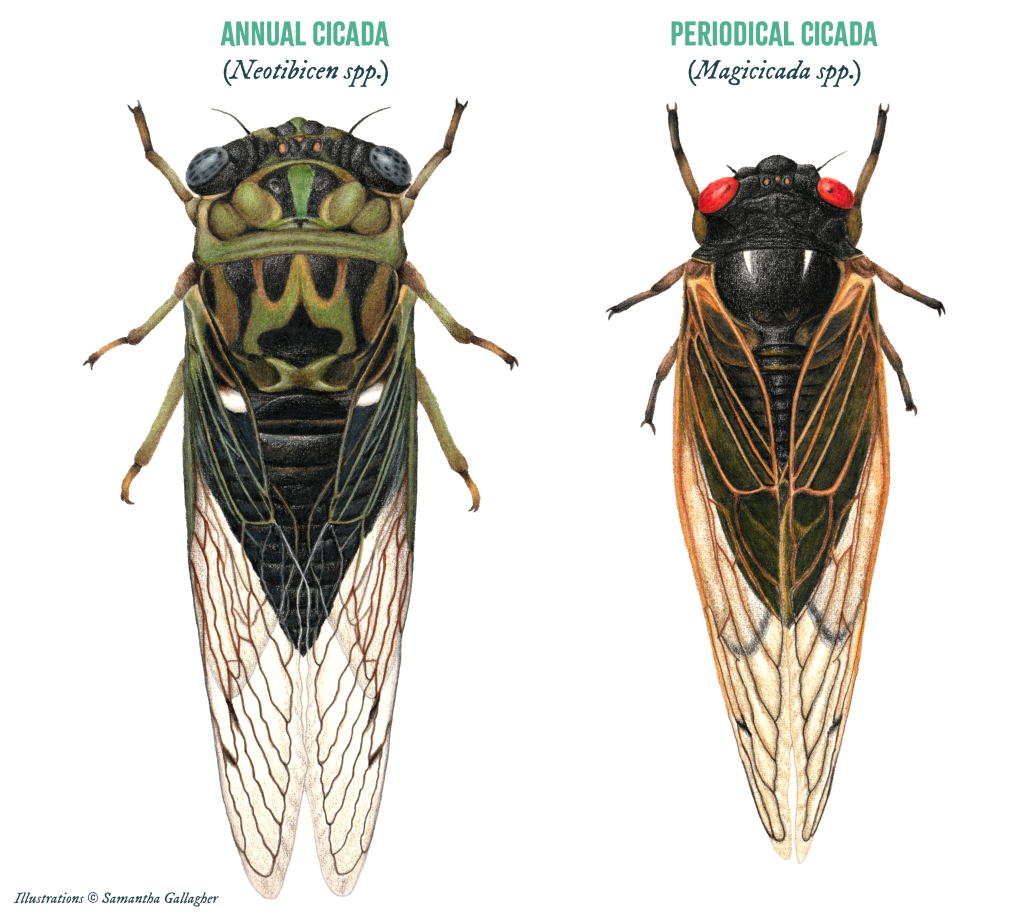

There are 190 known kinds of cicadas in North America and at least 3,000 species globally. All species of cicadas belong in the scientific order Hemiptera, a group of insects known as true bugs. A common trait among them is a “beak” used to drink fluids.

Most cicadas have life cycles of 2–5 years. Since species overlap geographically and aren’t synchronized, we observe some cicadas every summer. These are called annual cicadas.

Periodical cicadas live 13 or 17 years. Three 17-year species live in Lake County:

- Linnaeus’ 17-year cicada (Magicicada septendecim)

- Cassin’s periodical cicada (Magicicada cassini)

- Decula periodical cicada (Magicicada septendecula)

They’re harmless to humans and pets, and don’t bite or sting. Adults measure about 1.5 inches long. Except for different orange-brown stripes on their undersides, the species look identical. Learning their distinctive songs is the best identification method.

Linnaeus’ 17-year cicada produces a droning call that sounds like someone saying, “Pharoah,” with the first syllable extended: “Phaaaaaaaaaroah.” Some observers say it sounds more like, “wheeeeee-ooo.”

Cassin’s periodical cicada makes “a quick burst of sound, followed by some rapid clicks,” according to CicadaMania.com.

The decula periodical cicada produces a call with a tick, tick, tick rhythm that ends in less buzzy S-sounds, called lisps.

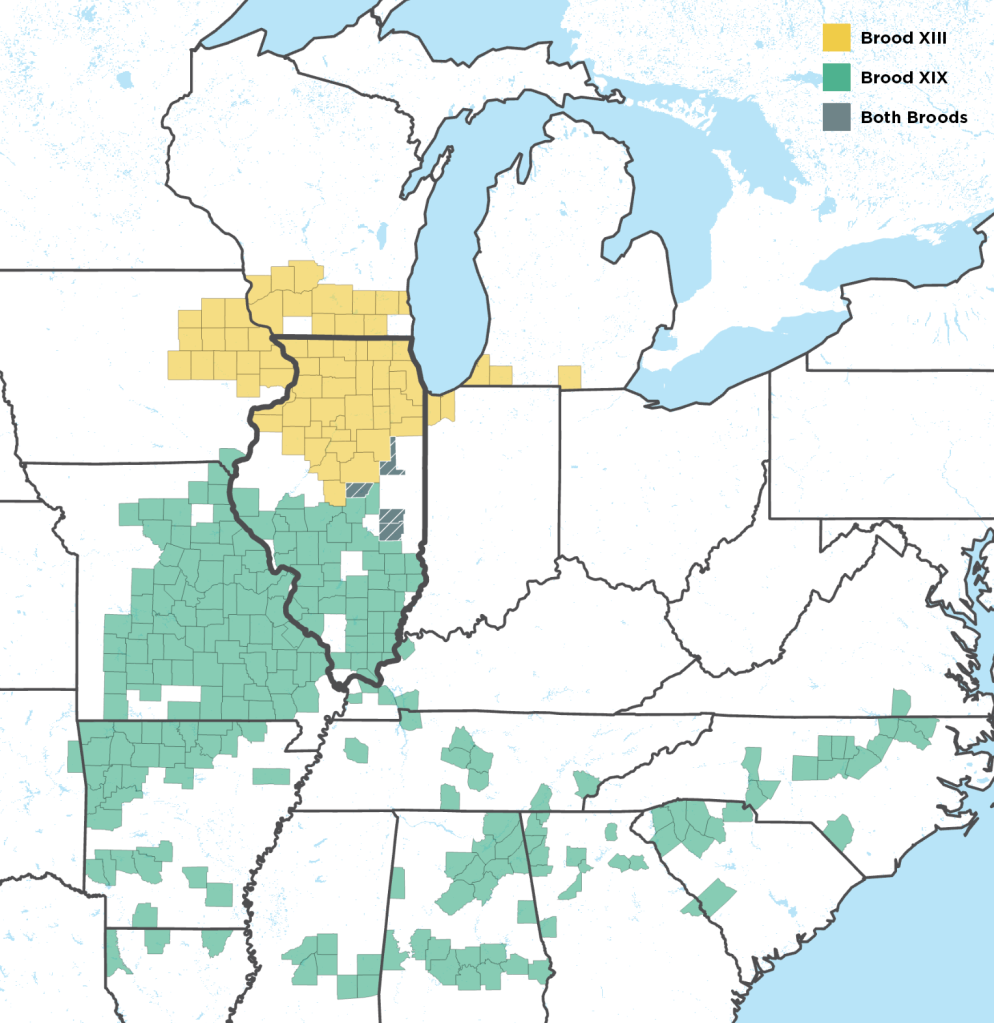

A brood is a group of cicadas that emerge together at regular intervals. Brood numbers are written as Roman numerals. Lake County’s periodical cicadas are in Brood XIII (13), spanning portions of Illinois, Indiana, Iowa and Wisconsin. Nationwide, there are 12 broods of 17-year cicadas and three broods of 13-year cicadas.

American Indians observed cicadas centuries before Europeans arrived. A 1634 journal entry by William Bradford, then governor of New England’s Plymouth Colony, documented cicadas.

“It is to be observed that, the spring before this sickness, there was a numerous company of Flies which were like for bigness unto wasps or Bumble-Bees,” Bradford wrote. “They came out of little holes in the ground, and did eat up the green things, and made such a constant yelling noise as made the woods ring of them, and ready to deafen the hearers.”

Brood XIII’s 17-year emergence coincides with that of Brood XIX’s (19) 13-year emergence for the first time since 1803, when Thomas Jefferson was president of the United States. Tecumseh’s confederacy, a confederation of American Indians living in the Great Lakes region, also began forming in the early 19th century.

Brood XIX contains four cicada species on a 13-year cycle. Nicknamed the Great Southern Brood, it covers portions of central and southern Illinois, Missouri, Arkansas, Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama, Georgia, South and North Carolina, Virginia, Tennessee and Kentucky.

Broods XIII and XIX will overlap most near Springfield, Illinois. They won’t meet again until the year 2245.

The Next Generation

Six to 10 weeks after their parents’ demise, trillions of rice-shaped eggs hatch where their mothers laid them inside shallow, V-shaped grooves near the tips of tree branches. The young, pale nymphs fall from trees and burrow into the ground. There they spend 17 years drinking sap first from grass roots, then deciduous tree roots.

Since sap is nutrient-poor, the nymphs grow slowly during this phase. Like humans, nymphs take almost two decades to reach maturity. In their homes 8–12 inches underground, they shed their brown exoskeletons, or protective shells, several times.

When ready for the final stage of their life cycle, two factors nudge the nymphs to begin their ancestors’ mating rituals. First, they sense the upward flow of sap, needed to sprout new springtime leaves, from the trees’ roots toward their crowns.

Then in late May and early June, once the temperature of the upper 8 inches of soil reaches 64 degrees Fahrenheit, the nymphs dig skyward.

They don’t emerge simultaneously. South-facing locations with plentiful sunlight will see the early bugs. Over several weeks, the cicadas will debut in such numbers they’ll be impossible to ignore. Rather, they should be celebrated.

Artistry and Entomology

We commissioned Samantha Gallagher, a local freelance illustrator, to create 11 original illustrations depicting the cicada life cycle. At her home studio in Lake County, the artist uses colored pencils, pastels and textured paper to showcase cicadas, bees, moths and more.

Samantha’s enthusiasm for insects earned her a nickname in second grade: the bee girl.

“I needed to get more people to realize how cool bugs were,” Samantha said. “People were especially scared of bees, and I really liked bees. And so, at some point in second grade, I got the whole class to be obsessed with bees, which was kind of funny. They even were calling me the bee girl. Other kids’ parents, who didn’t even know me, just knew of this kid in school who was the bee girl. And that was me.”

In adulthood, Samantha earned a bachelor’s degree in graphic design and a master’s degree in entomology, the study of insects. She blends them in her work today as a freelance illustrator.

Before pressing pencil to paper, Samantha consults insect specimens and reference photos, and visits local natural areas. The research phase can take a full day per illustration. She composes a digital sketch, traces it on paper and adds layers of color. Depending on size and complexity, she spends 8–20 hours fleshing out each drawing.

The results are beautiful, photorealistic illustrations.

“You’ve got to make it appealing to people,” said Samantha. “I can’t imagine thinking a cicada is not cute and adorable, but a lot of people think they’re disgusting, so you have to make them look charismatic and appealing and interesting.”

Samantha encourages observers to try to coexist during the emergence. Cicadas aren’t going to hurt you, and this happens once every 17 years.

“Imagine just sitting in a dark room by yourself for that long and just eating once in a while. So, the fact that they only get a month or two of glory after that dark period, just waiting and waiting and waiting. Don’t squish them,” Samantha said. “Be nice to them because they waited so long for this.”

Onwards and Upwards

Let’s get back to the cicada life cycle. We left off right before the nymphs were about to emerge. Once they’re ready to go, nymphs dig exit holes sometimes ringed by short chimneys. Soft spring showers help the process along. That’s according to Dr. Gene Kritsky, professor emeritus of biology at Mount St. Joseph University in Ohio.

“If you get a nice, soaking rain to soften things up, that’s when they really pop,” he said.

Gene, who’s sometimes called the “Indiana Jones of cicadas,” has devised a formula predicting the start of emergences.

“I have a formula I developed and published a few years ago that’s 90% accurate,” Gene said. “It uses April’s average temperatures to predict when in May the cicadas should emerge, plus or minus a 48-hour period. So, I can tell you a five-day window when they’re going to come out.”

Come nighttime, nymphs clamber up trees and other vertical surfaces. As if divers extracting themselves from wetsuits, they split open their exoskeletons once more.

“They split their nymphal skin, they slowly pull, they split the skin, they start to pull themselves out, eventually hang almost totally upside-down, pull themselves free, and then expand their wings,” said Gene. “Then they come out this sort of white adult and then turn black.

“This whole process, getting to this point where they’re out on the tree, is about 90 minutes.”

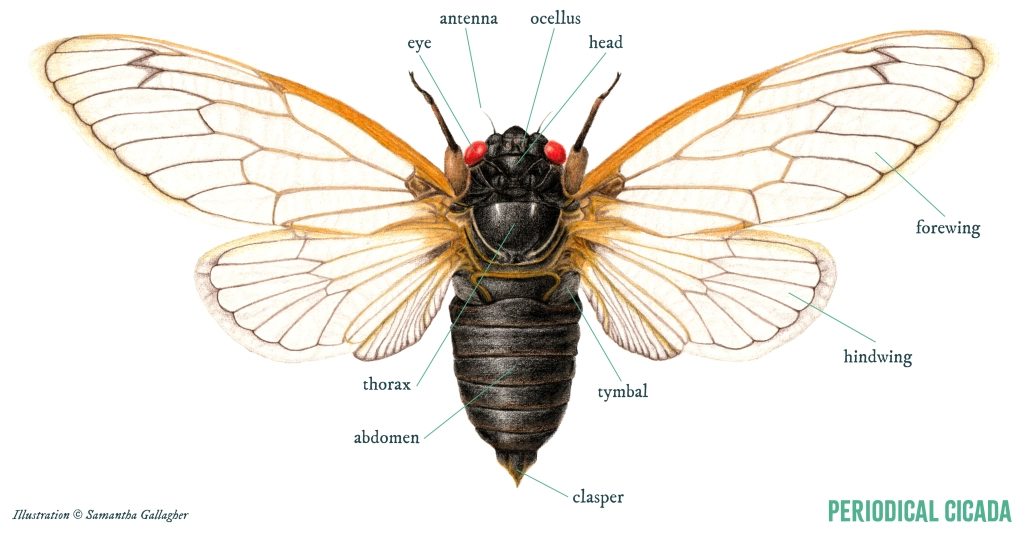

In this teneral, or soft phase, their squishy bodies are opaque white and yellow. Two black patches resembling a football player’s face paint mark their thorax, the middle part of their body. Perhaps most arresting are their red eyes with black pupils.

As Gene said, the cicadas expand their double pairs of orange-veined wings. Over 90 more minutes, their bodies harden and darken. Now adults, the cicadas crawl to the treetops.

“After they turn black, they crawl to the tops of the trees because they’re still not fully developed. The exoskeleton hasn’t hardened enough yet that they can actually sing or even fly. They’ll start flying over the next day or so, but they won’t start singing until between four and five days after they emerge,” Gene said.

Synchronized Singing

During daytime, chorusing centers of male cicadas sing using abdominal organs called tymbals. Tymbals expand and contract like bendy straws, producing clicks that swell into songs.

The male’s abdomen amplifies his calls to 90–100 decibels, as loud as a motorcycle. With up to 1.5 million cicadas per acre, the atmosphere will buzz with the peak of 17 years of patience.

“The males gather in large numbers in trees. They’re called chorusing centers,” said Gene. “The chorus attracts females ready to mate. When a male and female get close to each other, the male makes a call. The female flicks her wings to show she’s interested.”

This repeats a few times.

“After mating, she will—not necessarily right away, but over the next few days—go through the process of laying her eggs. She will have between 400 and 600 eggs. On average it’s about 500,” Gene said.

The female uses her ovipositor, or egg tube, to make cuts along branches. Mature trees in full sunshine surrounded by low vegetation are ideal.

According to Gene, “that’s why you tend to find more cicadas in parks and cemeteries and preserves, because that’s the ideal habitat for them. She’ll go along the branch inserting her ovipositor, laying about, oh, 20 or so eggs, walk another quarter inch down, do it again. The eggs take 6–10 weeks to hatch. And then it all starts over again.”

The symphony will continue for 4–6 weeks into July, until the adults die. When the eggs hatch and nymphs drop to the ground, the alarm will be set for 2041.

Prime Numbers

Why did periodical cicadas evolve such long life cycles?

They give the insect an edge over its predators, which typically have shorter life cycles.

The crunchy buffet represents a survival strategy called predator satiation. It’s safety in numbers. So many cicadas surface that predators—including birds, reptiles, mammals, frogs and fish—can’t eat all of them. It’s likely enough nymphs will survive to keep the cycle going.

The food bonanza has been shown to boost the populations of certain bird species such as red-bellied woodpeckers (Melanerpes carolinus) and blue jays (Cyanocitta cristata) by 10% for 1–3 years following a cicada emergence. Cicada bodies are also nitrogen-rich. After death, they decompose on the ground and provide nutrients to plants.

Some cicadas, known as stragglers, emerge in smaller groups one or four years earlier than their brood, or even four years later. Though rare, occasionally enough stragglers reproduce to start a new brood. This is called an acceleration. In 2020, this occurred in southeastern Lake County and northeastern Cook County. If the group reemerges in 2037, it will be known as Brood IX (9).

Experience the Magic

Most people will only see periodical cicadas emerge a handful of times in their lives. This will be just the second emergence to occur during my lifetime.

When the next one arrives in 17 years, I’ll be 47 years old. That realization has made the emergence feel even more special. It’s grounded my curiosity for what the future may hold more than many other things have in recent years.

Where will I be in 2041? What will I be doing? Will I be here to see the cicadas again?

These are unanswerable right now, but for that last one, I certainly hope so. Like the nymphs that will hatch this summer, I’ll have to wait 17 years to find out. And that’s all part of the fun.

So, what should you do during the emergence? Well, take some time to experience the magic. Enjoy this fantastic natural phenomenon and try to coexist peacefully.

Your forest preserves, plus parks, yards, neighborhoods and other areas with mature trees, will be cicada hotspots. Want to help track the emergence? Report your observations at LCFPD.org/cicadas.

Also, join us at public programs and events from April–June, including CicadaFest on June 9, 2024 at Ryerson Conservation Area in Riverwoods. See LCFPD.org/calendar.

And plan your visit to the Dunn Museum in Libertyville to experience the special exhibition Celebrating Cicadas, open April 27–August 4, 2024. Visit LCFPD.org/museum.

Want to listen to a version of this post? Tune into a special-edition episode of our award-winning Words of the Woods podcast. Available below and on Spotify, Apple Podcasts or wherever you prefer to listen.

And make sure to read the spring 2024 issue of Horizons, the award-winning quarterly magazine of the Lake County Forest Preserves in northern Illinois.