Post by Heather Johnson, Nicole Stocker and Brett Peto

This article appears in the winter 2025 issue of Horizons, the award-winning quarterly magazine of the Lake County Forest Preserves in northern Illinois.

Every acre in Lake County tells a story—often many at once.

Your forest preserves span 31,600 acres, including the traditional homelands of Native peoples. Indigenous cultures existed here starting at least 12,000 years ago, and the community maintains vibrant connections to the land today.

The Forest Preserves and its Dunn Museum in Libertyville partner with American Indian groups to guide us as we share the story of this area.

It Takes Two

“There are two sides to every story,” according to Kim Sigafus. “The one who’s telling the story and the one who is in the story.”

An award-winning Ojibwa author and speaker, Sigafus is a member of the Museum’s Native Peoples Advisory Group, formed in 2025.

Tom Smith, an elected official of the Brothertown Indian Nation in Wisconsin and a retired Forest Preserves stewardship ecologist, is also a member.

The group’s viewpoints help ensure Native voices shape our teaching. “Working with like-minded others helps gather the information and views from every perspective,” Sigafus said. “That’s the importance of the advisory group. We may not always agree, but we each have a perspective that is uniquely ours, and we are willing to share it with others.”

In August, she presented a program on Native harvest and traditional foods, explored through song, drumming and discussion. Sessions featuring Indigenous speakers and topics are among our most well-attended education programs.

“The telling of our story is important. We need to tell it in our own voice. It should come from us and not be told from a second person repeating what we said. It’s authentic and raw that way.”

Setting the Standard

History isn’t stuck in the past. It’s a dynamic science studying the historical record: documents, artifacts, oral histories, photographs, music and more. Combined, they help describe people’s lives at a certain time and place.

Museum staff continue to uncover new sources and use modern technologies to expand the stories we share, including the voices of underrepresented groups.

We invite the Native Peoples Advisory Group and other American Indian partners into the creative process from the start. Our educators put their advice into practice, updating programs and teaching methods for today’s learning standards.

Starting in 2023, state law requires Illinois schools to teach Native American history to students in grades 6–12. Lessons on tribal sovereignty and treaties, as well as genocide and discrimination against Native Americans, are required.

The Museum is a local leader in providing appropriate programs.

“Our role is to create space where Native voices are central and respected,” said Director of Education Alyssa Firkus. “By collaborating directly with Native partners, we ensure students and visitors connect with authentic perspectives, not secondhand interpretations.”

“Our role is to create space where Native voices are central and respected.”

Alyssa Firkus, director of education

Generosity and Guidance

Soon after entering the Museum, visitors turn a corner into the First Peoples gallery. There, a replica wigwam stands for them to enter.

Wigwams are dome-shaped, single-family homes built by the Potawatomi from bent tree saplings and sheets of bark.

We mimicked natural materials using durable, synthetic ones to avoid introducing pests. The wigwam hosts school and public programs where guests interact with replica Native American artifacts.

Highlighting the stories of Indigenous peoples in present-day Lake County and southern Wisconsin, the gallery reflects the guidance of George “Skip” Twardosz (1946–2023). He partnered with our Museum team as they designed new galleries ahead of the institution’s 2018 move to Libertyville.

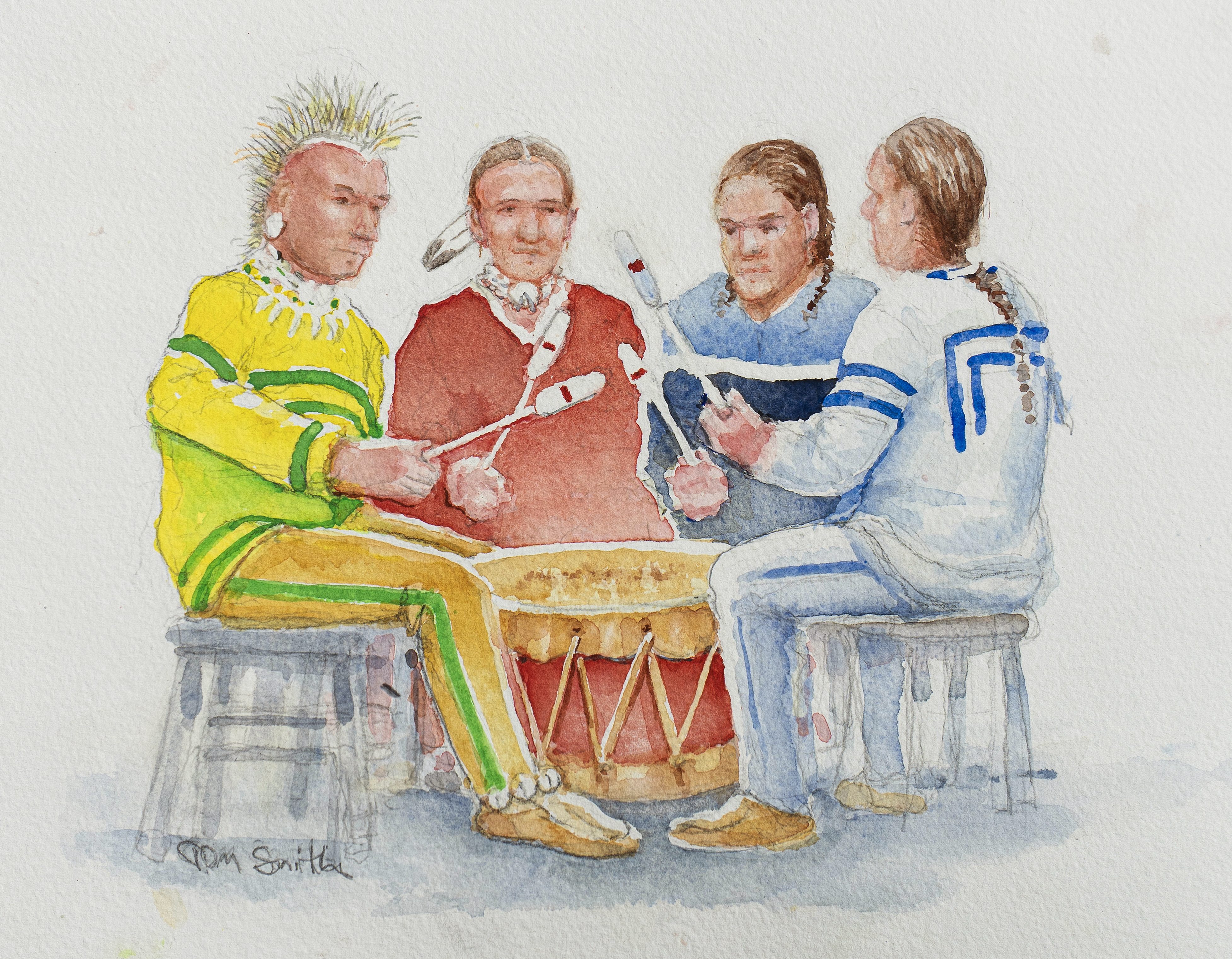

Of Potawatomi descent and historian of Woodland culture, Twardosz served as Storyteller, Fire Keeper and Elder for Native gatherings in Wisconsin, Illinois and Indiana. For many years, he also brought stories to life at the Museum with Gary Adamson, All Nations Tribe, through presentations with the Seven Springs All Nation Drum Circle.

“Staff really valued Twardosz’s warmth, wonderful education skills and generosity with his time and knowledge,” said Museum Education Manager Nicole Stocker.

After Twardosz’s passing in 2023, we worked with his family to create a plaque in the gallery remembering his priceless friendship.

Recognizing Connections

All our public events and programs taking place in a preserve or the Museum start the same way: by recognizing relationships between Native peoples and their traditional territories.

Starting in 2022, we collaborated with Twardosz, representatives from Trickster Cultural Center in Schaumburg and others to craft our first-ever land acknowledgment statement. They gave context for word choice, naming nations and understanding American Indian identity.

In 2024, our board of commissioners approved the statement. More than words, the statement is a teaching tool. It shares a bigger picture of human history in Lake County.

Land Acknowledgment

The Lake County Forest Preserve District acknowledges Native people as the original caretakers of the land it now owns. We recognize the role we have as a land management organization, dedicated to preserving the land and history of northeastern Illinois and we desire to honor the first people.

District lands are the traditional homelands of the Ojibwe, Odawa and Potawatomi nations. Many other nations have lived on, traveled through and welcomed others to this area.

American Indian groups still exist today despite the historical and cultural efforts of forced removal. They maintain cultural traditions and call Lake County home today.

The Forest Preserve District strives to build respectful relationships with Native American communities by seeking knowledge from Native peoples and providing programming about Native cultures and opportunities to connect to the land.

Cultural Care

What goes into preserving museum collections? You might picture secure, climate-controlled storage. That’s important, to be sure. So is cultural care—understanding the meaning objects hold for people who created or used them.

Many items came into the Museum’s care decades ago. In 1965, Lake County purchased the collections of the privately owned Lake County Museum of History in Wadsworth. These contained Native pieces acquired by the proprietors.

We invited Bill Brown, founder of the Potawatomi Trails Pow Wow, to consult on our collections care in the 1980s. The Pokagon Band of Potawatomi, the Sault Sainte Marie Tribe of Chippewa Indians, the Ho-Chunk Nation and Darrell Curlee Youpee (1951–2021) of the Fort Peck Tribes in Montana also contributed.

In 1990, Congress passed the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA) to strengthen protections for American Indian burial sites, human remains and cultural items.

It also outlined a legal process for Indigenous peoples to reclaim ancestors and sacred objects from any organization receiving federal funds. Dunn Museum staff at the time thoroughly inventoried Native collections, published notices and asked tribal nations to visit.

By 2018, we had returned all human remains and funerary items to the appropriate descendants.

If you find artifacts or other traces of Native peoples’ history in the preserves, follow these steps.

- Leave the object in place.

- Take a photo of the object in its surroundings. Record the location.

- Report it at LCFPD.org/contact.

Trained staff and Native partners will investigate the artifact.

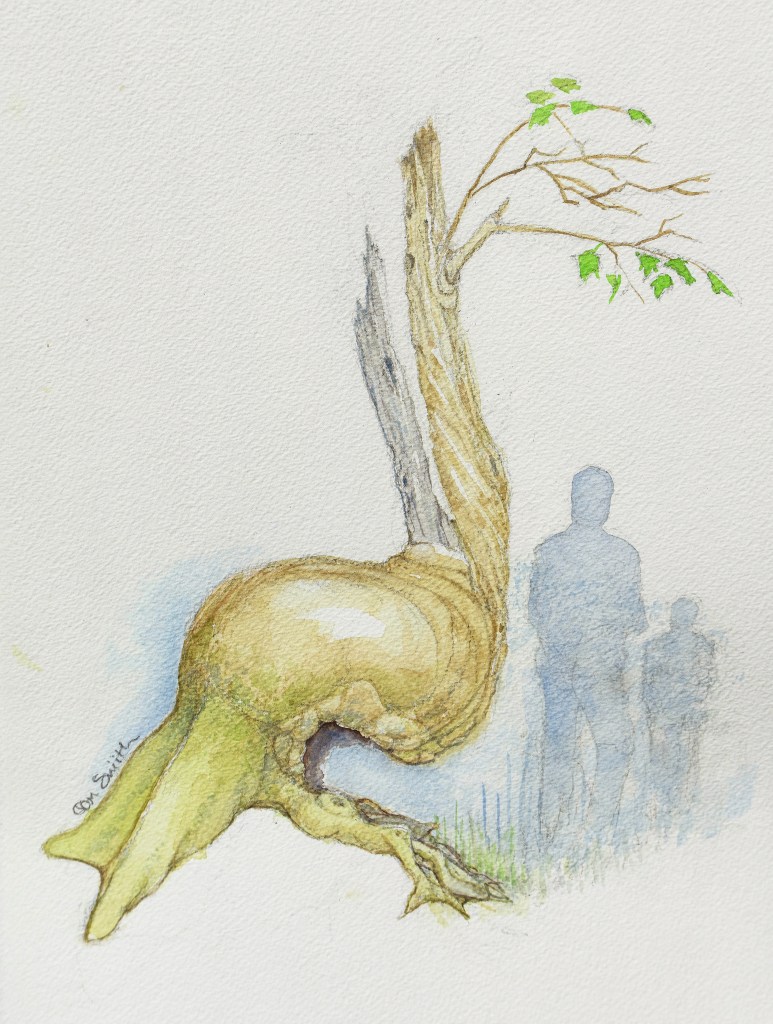

About the Artist

Born and raised in Lake County, Native artist Tom Smith worked with us for 34 years as a stewardship ecologist.

Painting watercolors is another of Smith’s talents. He studied the artform under Irving Shapiro (1927–1994) at the American Academy of Art in Chicago and credits Phil Austin (1910–2004), a Lake County watercolor artist, as an important influence.

Smith found inspiration in nature while painting backdrops for dioramas at the Adler Planetarium and the Chicago Academy of Sciences. His work has been shown in nature centers and museums.

Encouraged by our welcoming of Native voices and acknowledgment of traditional lands, Smith crafted several watercolors for this story. He created a luminous effect using transparent watercolor techniques.

Lake County’s Native Communities

Many tribes have lived in and traveled through Lake County, including:

- Ho-Chunk (ho-chunk)

- Illinois (il-ə-NOY)

- Kickapoo (KI-kuh-poo)

- Menominee (me-NOH-muh-nee)

- Meskawki (mess-KWAH-kee)

- Miami (my-AM-ee)

- Odawa (ow-DAA-wuh)

- Ojibwe (ow-JEEB-way)

- Peoria (pea-OR-ee-uh)

- Potawatomi (pow-tuh-WAA-tuh-mee)

- Sauk (SAWK) and Fox (FOKS)

- Winnebago (wi-nuh-BAY-gow)

New Chapters

Even 35 years after becoming federal law, NAGPRA still shapes practices nationwide. A final rule introduced in 2024 set new standards on the duty of care for Native American artifacts. Organizations must consult with “lineal descendants or a culturally affiliated tribe” before exhibiting or making Native images or objects available. This prevents physical or spiritual harm.

We carefully reviewed the First Peoples gallery and updated our collections policy in the wake of this rule. Now, we accept Native items only if they’re offered by—or in consultation with—their creators, descendants or affiliated tribes.

So, the stories of Lake County’s Indigenous peoples continue. They forge ahead in time, in depth, in respect. New chapters are coming.

For the Forest Preserves, the Native Peoples Advisory Group is an essential author.

“Our responsibility is to listen and collaborate, so we reflect the voices that have always been here,” said Firkus.

Images © Tom Smith, John Weinstein.